Last week I visited ‘Write, Cut, Rewrite’ at the Bodleian Library in Oxford. Sadly I caught it on the last day, and not everyone can just pop over to Oxford on the train anyway, so for those who missed it here are some reflections from this fascinating exhibit about the authorial editing process. There’s also a book you can order online which goes into the exhibit and more.

Last week I visited ‘Write, Cut, Rewrite’ at the Bodleian Library in Oxford. Sadly I caught it on the last day, and not everyone can just pop over to Oxford on the train anyway, so for those who missed it here are some reflections from this fascinating exhibit about the authorial editing process. There’s also a book you can order online which goes into the exhibit and more.

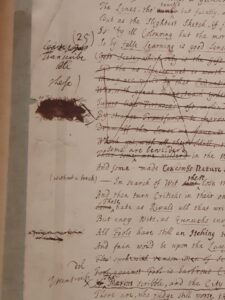

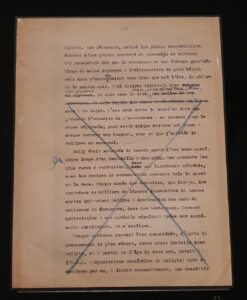

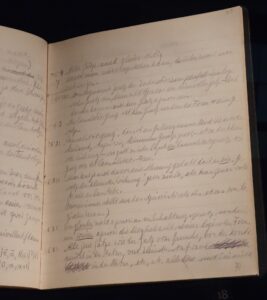

I’ve often wondered how editing worked before laptops and email (I recognise this was not that long ago!) – and even before typewriters (longer ago). Without the ability to edit endlessly, copy and paste, delete and un-delete – without having to tippex or rewrite your whole manuscript again from scratch – how much did authors edit their work? I presume that without the ability for editors to send you endless rounds of feedback, most editing was done between the author and their manuscript, and the correspondence with the publisher must have consisted of only one or two rounds of comments at best. But did this make for worse writing, or better works of fiction? Now there’s a question!

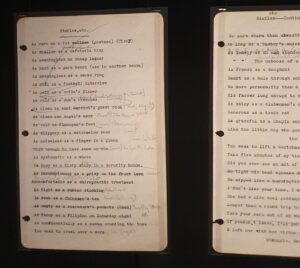

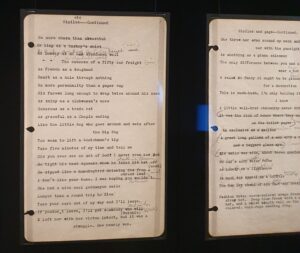

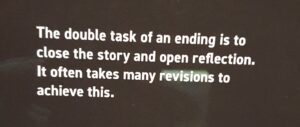

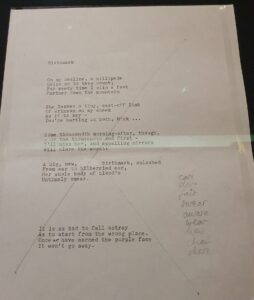

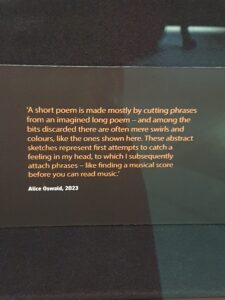

The exhibit itself spans present day writers and poets who do have the option of typing on-screen, and those who had no choice but ink and handwriting. What is common to all of them is a reassuring obsession with precision of language, tweaking round the edges – sometimes for obvious effect, sometimes less so – and on-the-page evidence of a mind at work, finding, refining, and polishing to reach an end product that satisfies. My personal favourites (see below) were the examples of authors who offered further tweaks on the Foldings & Gatherings (initial printed pages) and even after the first edition was out (the removal of a single comma – a man after my heart). Overall, having spent a significant amount of time playing around with commas, changing a word and then changing it back again, it made me feel a little more sane – and in the company of greatness!

Highlights from the exhibit

1. For the second edition of ‘A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man,’ Joyce asked for this one comma to be removed.

There were also lots of examples of authors changing their openings (fascinating development of the opening of Le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy) and titles (The Wind in the Willows was originally The Rat and the Water Vole, for example).

What about Fledging?

As I walked around the exhibit, I couldn’t help thinking about some of the edits I did and didn’t make to ‘Fledging,’ whether of my own accord or on the advice of others – my beta readers, Indi Novella (a fantastic publisher and writing hub that mentored me on my draft and helped me find my agent), my agent Laetitia Rutherford, or my publisher Renard Press.

So what did I change?

A few examples:

– I deleted, then re-added, then sometimes deleted again, more commas than I can count… including in the final sentence of the novel, which was the subject of heated debate between me and Will at Renard!

What stayed the same?

– As those who’ve heard me give a reading of it will know, the opening scene actually changed the least out of any section of the book. I changed a few words here and there, but in the main it stayed mostly the same. Like the egg, it seems the scene just came from somewhere inside of me. And readers always seem so taken by it, there was no reason to meddle too much!

– The title! OK, so the original working title was ‘one in a million’ (in reference to the tiny chance any of us have of being conceived and coming into existence). But very early on I changed it to ‘Fledging.’ I had heard that agents and publishers almost always change the title. And for a long time I was worried about it – was it too similar to Octavia Butler’s ‘Fledgling’? Would people continue to misspell it and mispronounce it as ‘Fledgling’? (Answer: yes). Did anyone even know what Fledging meant??? However, after much brainstorming in my notebooks, and discussion with Indie, then my agent, then my publisher, it somehow stuck at each stage. It just worked. At least we thought so!

What did I learn about editing?

Fledging is not the first novel I’ve finished, it’s just the first to be published. So a lot of these lessons I learned from my previous manuscript, which was also not the first manuscript I finished, but the first I’d say I took really seriously – and took through beta readers and multiple drafts.

But nonetheless here they are:

1. Rhythm matters. I don’t know what it is but somehow after I’d made Lia a songwriter and started sprinkling the book with musical metaphors, I became more conscious than I ever have before of the rhythm of sentences. It’s not that I wasn’t aware of this at all previously, but it became even more important to me. I’m not saying that every sentence of Fledging is perfect – there are still sentences that frustrate me, but I like to think I’ve got at least the most important ones right.

2. Don’t panic. Sometimes you’ll get feedback and dive into despair, thinking you have to rewrite half the novel. OK, sometimes you do. But often the edits needed are not as big as you think. Often it’s as simple as a few words or half a sentence here and there, sprinkled throughout the book. Trust your reader – they remember and pick up on more than you think. A few words can have a big impact. Less is more.

3. Push yourself. Working with my agent was eye-opening. She picked up on all those sentences and words that didn’t feel perfect but felt good enough, and pushed me to come up with something better. It was infuriating when I was staring at my laptop at 3am in the middle of a work trip, trying to think of a better simile. But she was right. It made Fledging a better book. For me, that was a huge part of the value of being traditionally published – the number of rounds of editing that Fledging went through. That’s not to say you can’t self-publish and have a really quality book. But just that you need to find the other ways to push yourself – think of it like hiring a personal trainer.

4. Check you’re achieving the effect you think you are. This one was from Damien Mosley at Indie Novella. There was a particular phrase I liked that he suggested changing. I explained why I thought it was important, and that’s the right thing to do – you shouldn’t just take feedback without questioning it if you disagree. BUT the key thing he said to me which I found so helpful is: ‘sometimes what you’ve written isn’t having the effect you think it is.’ If that’s the case, then think about changing it so that you do achieve that effect. Excellent advice.

6. Cut unnecessary words. This is an obvious one, and will depend a bit on your style. But it’s still important. You want your reader to get to your story and your meaning in direct a way as possible. Unnecessary, empty words get in the way of that. There are lots of reasons words may need to be there – to add nuance, to add colour, perhaps even to add rhythm. But really test yourself on whether they’re doing that. If you could remove them from the sentence without changing the effect, delete them. Empty words are only a distraction. Oddly, this is one thing from my working life which has helped me in my writing life. At work, I have to communicate in a very clear, simple, succinct way, often to very strict page or word limits. I’ve become a pro at spotting the words that aren’t needed – and playing a little tetris tune in my head when I remove them. It’s a skill I now apply (with a bit of lenience) to my creative writing too.

6. Don’t use song lyrics. Inspired by Lia’s songwriting ambitions, Fledging originally had song lyrics woven throughout, sometimes explicitly, sometimes less so. Then two things happened: I learned this was a copyright minefield, and my agent challenged me to be more original and use my own words. I still sometimes mourn the loss of this aspect of the book (though there may be one or two easter eggs left if you look very closely), but overall it was the right decision. I’d rather not be sued, and once again, Laetitia being cruel to be kind did force me to put things in my own words.

7. The ‘Frozen’ Rule: Let it goooooooo. At some point you have to accept that you can’t have every sentence perfect if you ever want to finish the goddamm thing and get it published. Also, mistakes happen. The first edition of Fledging had a typo. I spent a moment getting crazy over it. Then learned that none of my readers had even noticed. Even now I think of little tweaks I might like to make. But the book is what it is – it’s a snapshot of how I wanted it to be at the time. New thoughts can go in new books. There’s always more to write!

Fellow writers, what are your top tips for editing?